Henry at the 23rd Marine’s base camp in Maui, 1945

(Third in a family legacy series. In the second, I tried to imagine what Mom’s experience must have been like on the home front, which I titled, “My Mother’s War.”)

Like many men of the Greatest Generation, Dad was always quick to deflect attention from his accomplishments during the war. The real heroes, he said, were the guys who were wounded or died. As a child, I morbidly wondered if he ever killed someone. So far removed was it from my experience that I thought of it like something from a movie. I never found out if he did, never asked him, perhaps because when the topic of the war arose, there was always a pause. For a moment he seemed far away, remembering scenes, perhaps. Or people.

Only in the last 15 years of his life did he share information about his role during the war. Even when sharing relatively lighthearted stories, he would often be moved to tears as memories welled up.

After instructing recruits at the base in Quantico for two years on rifle marksmanship, bayonet training, mortars, map reading, nomenclature, and cleaning of all the military weapons, he received orders to join the 23rd Marines, 4th Marine Division in 1943.

He was to serve as R-4, Regimental Supply Officer.

When I was young, I didn’t think being a supply officer sounded very exciting. But Dad would put it in context for me, explaining, “Your intelligence officer tells you what the enemy can do, while your supply officer tells you what you can do.” The supply officer’s job is to ensure combat readiness by having the personnel and materials in the right place at the right time to achieve the combat objective. The lack of food and supplies confounded Gen. Robert E. Lee on his northernmost advance to Gettysburg, and we know how that ended. Had the Confederate Army had adequate supplies, things might have turned out very differently.

Dad’s explained his first assignment, loading a ship in San Diego in preparation for the 4th Marines’ deployment to the battle lines in the Pacific in December 1943 or January 1944:

“I was told to take a communications group and establish an advance command post with about 15 guys. Rhett Williamson was S4 Supply and Logistics Officer. …He had stuff coming from five places. The first time I know about it is a truck shows up at the gate for instructions. We start getting these loads of stuff. Loading should have been pre-planned. Rhett isn’t down on the docks. It’s chaos unless I do something about it. This went on for 10 days. When we got through, we were the only ones in the U.S. who knew what we had and where it was. Louis Jones, Regimental Commander, asked Rhett what was going on and kept him standing there until 4 a.m. Then he said, “Campbell, you are now R4 (Regimental Supply Officer).

“We got it all on there. At 2 a.m., I got a call at the gate. ‘We have a load of explosives on there.’ The Commanding Officer said he didn’t want any explosives on the base without him knowing about it. So I called him at 2 a.m. I never heard from him again.

“At 6 p.m., we’re all loaded up. We were supposed to leave at 8 a.m. At 7 p.m., a truck shows up with ammunition. I asked him what was in the trucks. He said enough for a round of fire for an entire regiment. So I told them to unload the ship, put everything on the dock, and put the ammunition in the boat.

“That’s how you load a ship. You figure out what you need in terms of beans and bullets. You figure out what you need first and put them on last. We disembarked right on time.”

According to John Costello writing in The Pacific War 1941-1945, the 4th was to participate in Operation Flintlock, the plan to assault Japanese positions in the Marshall Islands that were being used as bases for ships, submarines and air staging. The battle plan was hotly debated because of the bloody lesson of Tarawa, which had resulted in heavy losses.

The plan called for attacking two positions in the Kwajalein atoll. Roi-Namur, the northern objective, was made up of two islands connected by a narrow causeway. In alignment with battle tactics learned the hard way based on the first two years of the war in the Pacific, the islands were blasted by battleships for three days before the amphibious landing.

Now S-4, Dad’s job was to get materials ashore. He secured a boat driver and chose to land supplies after the first wave of infantrymen but ahead of the next wave. Company Commander Shelton Scales’ jaw was said to have dropped when he landed on the beach and found Dad there ahead of him. The attack that began on Jan. 31, 1944 was mopped up by Feb. 3.

Saipan was a challenge of a different order. The Battle of Saipan was part of “Operation Forager,” which aimed to sieze Saipan, nearby Tinian and recapture Guam in the Marianas. According to Costello, “Operation Forager’s 535 ships and the 127,571 troops assigned to the American assault in the Marianas made it not only the largest force yet assembled for any naval operation but also the instrument of a new phase of the war.” Now American troops would attack well-defended bases of Japan’s inner defense line rather than pulverize atolls.

Bombardment began June 13, 1944, and D-Day was two days later. With over 3,000 killed and 10,000 wounded, it would become the costliest operation for American forces to date – but that cost paled in comparison to Japanese loss of life. Five thousand Imperial Army soldiers died in suicidal Banzaii attacks, and an estimated 22,000 civilians died, principally because their shelters were in harm’s way and indistinguishable to Marines who cleared suspected bunkers with explosives. Even more horrifying, an estimated 1,000 women and children jumped off a cliff to their deaths based on orders from Emperor Hirohito suggesting they would be heroes on a par with soldiers in the afterlife if they did not surrender. Taking Saipan took six weeks.

Dad received his first Bronze Star in 1944 for his efforts on Saipan. The citation read: “By his initiative, perseverance and outstanding ability, he not only provided by proper planning for the supply of his organization but during the early phases of the Saipan operation while beaches were congested, under heavy hostile gunfire, and threatened by Japanese counterattack, he through several sleepless days and nights not only insured the combat supply of his own unit, but also supplied other units for whom immediate supplies were unavailable…. During the entire operation on Saipan, lasting for a period of approximately one month, never once did his regiment suffer for lack of supplies or equipment.”

As costly as Saipan was, it brought Tokyo within range of B-29 bombers.

Operation Forager continued when, two weeks later, two Marine divisions landed on Tinian on July 24. Costello wrote, “Inside a week the Marines had won control of Tinian with only four hundred casualties, in what General Smith was to call ‘the perfect amphibious operation of the Pacific War.'”

Here’s how Dad described it to me in 2000:

“Tinian was heavily defended. Although there were good landing areas on the south side of the island, at the Corps level, they decided against landing there and instead chose a small landing beach about 100 yards wide. They figured they could get people on the beach and it wouldn’t be defended.

“D-Day was 7 a.m. Scads of landing craft were offshore. My regiment was in reserve for landing since they were part of the assault on Saipan. They were supposed to move in behind the initial troops. The initial landing proceeded okay. The 2nd regiment was supposed to land – to come through us and proceed. We were supposed to wait until after they were off of the causeway.

“I borrowed a jeep and talked to Col. Jones. He said, ‘Campbell, I want all communication vehicles and anti-tank guns ashore.’ I took a boat to talk to the control officer, Col. ‘Jack’ Horner. Col. Horner said, ‘Campbell, I’ll get to you as soon as I can. I have to land the 2nd regiment ashore.’ I told him, ‘Col., we’re astride.’ He said, ‘Campbell, I told you I’d let you know—now goddam it, get off my boat.’ I looked for a hole and put my men ashore. When I told Col. Horner later, he threatened court martial.

“The main attack came in that night. Regimental guns killed 600 Japanese that night with 36 mm anti-tank weapons that shot canisters of grape shot. It didn’t last long. Our counter-attack broke their back at the end of August.

“We found beer in a Japanese dugout. Every man in the regiment got a bottle of beer and the rest went to Division.

“Saipan is where the Japanese jumped off a cliff rather than be captured. They believed they would be tortured by the U.S. The remaining pockets of resistance ranging from squad- to platoon-sized raised hell – it was really dangerous. Our battalions were spread out on the North end. At night we formed a defensive perimeter.

It was on Saipan where Dad experienced what he called “the hairiest situation”:

We had overcome the emplacements and had set up three or four encampments along the plateau. At night, the Japanese who were still loose on the island would open fire. Every night gun battles would break out. LtC. E.J. Dillon, who was no friend of mine, would call and tell me he was out of some supply – like illuminating shells. I was the supply officer, and it wasn’t really my job to get it to him, but as the senior supply guy, I felt responsible. So I’d reconnoiter a jeep. It galled me that I didn’t have one assigned to me like some officers who could swan around in theirs with some burly guy sitting on top of the supply boxes with a BAR. This required going across ‘no man’s land,’ the narrow perimeter of the island. I’d been over the road once but I really burned rubber with a 45 in one hand. We’d head out in the dark down the long road to deliver the shells. I could imagine an ambush anywhere. Never had a problem but I sure felt grateful to have my skin by the time the war was over.”

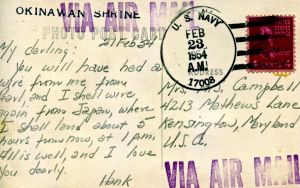

Henry’s V-mail to his parents on August 3 from Tinian:

It’s been a long time since the last letter, and since I wrote it, the battle for Tinian has been fought and won, although we are still mopping up. Things will relax a little now, I xpect, so you can expect to hear from me with more regularity than in the past.

This will serve to do little more than advise you that I am perfectly OK, and so far unscathed. The Tinian fight has gone considerably easier than Saipan, but I’m glad that it’s over – it was officially announced secured night before last, although mopping up still continues.

You letters – from all of you – have been arriving as the mails do, and they are always eagerly read. I’m glad Eileen could be with you as long as she wash – wish I could have been there too. However, even though I could not, I feel I was well represented. It must have been a lot of fun, and from your letters and Eileen’s, everybody had a pleasant time of it.

As for myself, I am – as I said OK, and am at the moment enjoying a little relaxation. That won’t last, of course, — R-4s, like woman’s work – is never done. Any staff officer is in that position.

Sometime soon I expect I’ll be getting around to putting own on paper such account as I can give of the Saipan and Tinian operations, but don’t look for any spell-binding report. It’s mostly hard work, the excitement is occasional, and then not very exciting in the re-telling.

I send you all my love. It is a wonderful feeling to have a family like mine safe at home.

Your loving son,

Hank

Source: The Pacific War: 1941-1945, New York: Atlantic Communications, 1981, p. 669

The 4th Marine Division had a chance to recover after Operation Forager’s success, not seeing action again until February 19, 1945. Other Marine divisions, however, were plenty busy, especially on Peleliu where the 1st Marines engaged in battle that was bloodier and more grueling than Guadalcanal. Col. Chester “Chesty” Puller’s 1st Regiment clawed up a cliff, under fire from Japanese who rolled grenades down on them from caves, gulleys and holes, costing the regiment a third of its strength. Peleliu was taken on Nov. 25, 1944.

According to Richard Newcomb, author of Iwo Jima: The Dramatic Account of the Epic Battle that Turned the Tide of World War II, it was inevitable that the Allies would have to take Iwo Jima. To attack Japan, it would need the island as a fallback for B-29’s. Iwo Jima was the only island in the area capable of supporting several airfields, an objective of the mission. It would be the first American attack on Japanese home territory.

When Dad talked about Iwo Jima, he usually started by describing its long, narrow beach of volcanic ash (described as a sticky, glue-like substance) over which Mt. Suribachi and the cliffs loomed, riddled with Japanese defenses. Iwo was a stone fortress. Violating Japanese military doctrine, the island’s defenders developed a plan to wait until Americans had penetrated 500 yards onto the island. Then and only then would weapons open fire from the airfield, supported by artillery on Mt. Suribachi and the plateau. Sixteen miles of tunnels connected Japanese concrete artillery emplacements. After initial fire, the guns at the airfield would withdraw to the north.

Bombardment of Iwo began on June 15, 1944. The 4th Marine Division began landing at 8:59 on D-Day, February 19, 1945, against high winds and four foot surf. Here’s how Dad described it in 2000:

“When we pulled in offshore, the light was growing. You’re up on the deck. You see this ungodly ghostly tower rising 600-700’ in the air. It was a volcanic spire, the goddamnedest thing I ever saw. Scary.

“The island was shaped like a pork chop. It was a volcanic mound with steep sides, honeycombed with caves. It overlooked the beaches we landed on – the Japanese had perfect visibility. Down at the far end was another escarpment looking the other way. We had one fine officer who took a posthumous award for scooping up men without leaders and taking the key point (Chambers). They got all shot up.

“High velocity anti tank guns were looking right down at the beach. It was probably 500 yards or more from shoreline to airfield. It was D+2. We were in a pillbox, our first command post. The gun opened up. There was a tremendous concussion over my head, sand came down. I think a round bounced off the ground on top of the command post.

[The 4th Marine Division could only advance some 50 yards on D+2 as it pushed northward, experiencing high casualties as it attempted to clear pillboxes, caves and tunnels.]

“The next night, the Japanese had mortars – 240 mm – as big as a trash can. You’d see it go up. You wouldn’t know where it would come down. They dropped one about 30 yards outside the pillbox. It lit into a crater where we had 15-16 people. Just like that, they were gone. We lost some very good men, some who were friends of mine.

[By the end of D+3, the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions had suffered a combined 4,574 casualties.]

“The longest walk I ever went on – I don’t know how far in miles or yards – was on Iwo Jima. We were in reserve because we’d been all shot up. We’d probably lost a third of our troops by then. My job is to prepare to take over, so I need to know where everyone is, their weaponry, etc. I had to walk alone to the command center from my division’s headquarters. It seemed like miles, but I wonder how long it really was. I went to collect our orders and check the situation map. The map was surrounded by people and it was hard to get much of a view. Periodically, however, the Japanese would start shelling and while everyone scattered, I could copy the map. Worked great.”

Iwo Jima, and its specific objectives, earned gruesome nicknames – the Red Island, Blood Beach, etc.. The 4th Marine Division faced formidable defenses in Hill 382 (for its elevation), which would become known as the ‘Meatgrinder.’

Although American forces had overwhelming superiority, Iwo Jima was the only battle by the Marines in which the overall American casualties exceeded those of the Japanese. American losses reached 6,821 with another 19,217 wounded. Dad received his second Bronze Star with “V” for Valor for his efforts as operations officer, 23rd Regiment, 4th Marine Division.

For its actions against enemy forces during the war in the Pacific, the 23rd Marines received the Presidential Unit Citation Streamer with one Bronze Star,the Navy Unit Commendation, the American Campaign Streamer with four Bronze Stars, and the World War II Victory Streamer.

The 4th Marines were pulled back to base camp on Maui to reconstitute their ranks, which had been decimated by the campaign for Iwo. After receiving an ultimatum threatening Japan with “prompt and utter destruction,” American airman dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6 and on Nagasaki on August 9. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced his acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, kicking off a national frenzy of celebration and kissing servicemen. The Instrument of Surrender was signed by the Japanese on September 2 aboard the USS Missouri.

It’s hard to imagine that the war did not change Dad. It must have. But as he explained to Mom in a letter, “…it is as if there is a hard shell around me and that ALL of this present life went on outside me.”

He came home.