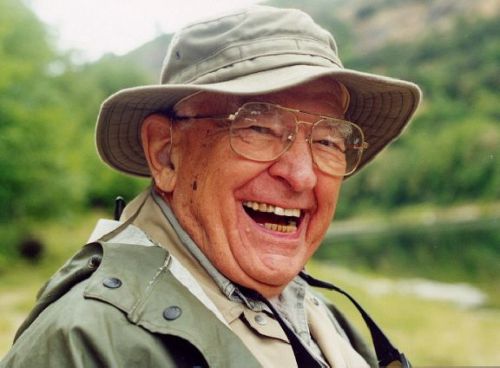

My father died five years ago today at ninety-six years of age. I feel his presence still, and I hope I always do. Here’s what I shared at his memorial a month after his death:

There are many ways to look at my father’s long life. You can look at it through the lens of history. He remembered having one of the first phones in Yakima with its three-digit phone number, and died in a world that had been transformed by technology. You can look at it through the lens of medicine. He was a walking miracle who lived 50 years after his first heart attack, having survived three open heart surgeries, two more small heart attacks, and three strokes. You can look at his life through the lens of professional accomplishment, a tough, smart Marine who was twice decorated with a bronze star with V for valor and who was unafraid to challenge his superior officer even when threatened with court martial.

But I think of my father’s life as a love story. He was a middle child in a difficult family. He loved his mother deeply but feared his father, who he referred to as “The Great I Am.” Dubbed “the smart one” by his family, he was accelerated in school by two years, which he said was a disaster for any young man with an interest in young women. He didn’t stand a chance.

After a stint in junior college, giving him a little time to grow up, he went on to University of Washington, where he began to come of age. He stumbled at first, distracted by things like an Alpha Delta Phi fraternity brother’s willingness to sneak him in and others in to the Rainier Brewing Company’s tap room. When his inattention to grades earned him the wrath of his father, who threatened to take him out of school, Dad wrote, “…right now there is nothing I want so much in the world as the faith, love and respect of you and Mother. If I cause you to lose that, then I frankly feel no purpose in pursuit of life, or any further exertion, because when those things go, with them goes my self-respect, and that gone, I should have nothing.”

In his writing, you could hear the words of a romantic. Meant to be the family lawyer, he was in love with words. He began to devour and memorize large swaths of poetry, with favorites including Shakespeare and 19th century poets.

Then he met my mother, and the next chapter in his love story began. As my Dad told the story, it was spring of 1939 at the UW, Dad’s senior year. The story was always told the same way: after drying himself out from a binge in the taproom, he seated himself in Dr. Padelford’s class on Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning where they would study “The Ring and the Book.” Whereupon he saw “this vision enter the room, dressed to the nines.” As my grandfather said when he met my mother, “Son, a pretty face will fade away, but a good pair of legs will last forever.” Soon the cherry blossoms were in full bloom on the quad, and the girls shed their bulky sweaters and began walking around in diaphanous skirts.

If ever an immovable object met an irresistible force, it was my father meeting my mother. My mother, upon learning that Dad was pinned to a girl in Yakima, handed him $5 for train fare and told him not to come back until he had the pin. In 1941, after Dad had been commissioned as a second lieutenant and was stationed in Quantico, Mom sent him a cryptic telegram saying that she accepted his proposal and was heading east with her mother to get married. He swore that he had no recollection of any such proposal. My father, concerned about the limited longevity of second lieutenants during war time, didn’t want to start a family; but my mother told him in no uncertain terms that he was not going to go off to war without him leaving a piece of him behind, and in November 1942, Scott was born.

Fast forward to 1999. Though I knew of Dad’s love of poetry and Mom, I don’t think I truly understood how driven he was by love until after Mom died. If I may mix my metaphors, when my mother met my father, they were two elements that combined to form a compound. (I’m no chemist; I’ll let you figure out which two elements.) I didn’t have a lot of insight into my father’s experiences and feelings until after his life-long confidante was gone.

At the end of Mom’s 3 ½ month illness with late stage lung cancer, at sunset on May 10, 1999, I called my father in to their bedroom after I noticed that Mom’s color had changed; while I called hospice, he held her hand, told her that he loved her and that he would be with her again. Then her heart stopped.

As we sat together in the days that followed, recollections began to spill out from him.

First he recalled Mom. As I wrote later, “In the days after my mother died, my father recalled some of their intimate moments like movie images, how she looked with the glow of moonlight on her body.” It would have been a beautiful moment were I not trying to block that image out of my mind….

Then he began to talk about the war, something he had rarely done throughout my lifetime. He described being in the Japanese pillbox that had been cleared and that served as the command center on Iwo Jima. A huge shell went off just outside. He pointed from my parents’ front door to the dining room and said that the shell left a crater that large. He said that some fine men were obliterated by that shell, many he knew, some he was proud to call friend.

But the most difficult memory he shared with me was that of the final illness of my sister, Midge, in 1953. Dad sat on the couch and described her in her oxygen tent in the hospital, reaching out her arms toward him, and saying, “Daddy, help me.” He said that he went out in the hall and pounded on the wall with his fists. “I could do nothing,” he said. As he told me the story, he repeatedly slapped his forehead, not gently, but hard, crying. I finally took his hand and told him to stop hitting himself.

In 2006, I invited Dad to move to California, figuring that he was, as I put it, “past his expiration date.” The cardiovascular surgeon who operated on him in 1999 had projected that the surgery would give him lasting relief for only about five years. Then his heart disease would likely end his life.

The ensuing seven years were transformative, for Dad and for me. I listened as he worked through the most important experiences in his life. His love of Mom. The War. The Loss of Midge. His difficult relationship with his father. His love of his mother. Like all of us, he had regrets or things he never understood.

He softened. When I once commented that he seemed to have become more gentle and less judgmental as he aged, he said, “Who am I to judge?”

Perhaps my father’s biggest challenge was his final one – the grueling march of his final years.

His physical abilities were seared away by time. He lost his hearing. His balance faltered. His chest pain increased. His breathing became strained. It became brutal to watch.

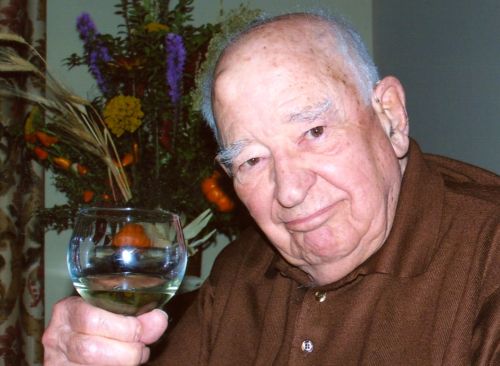

But what remained was Henry, distilled and pure. He loved red roses, which represented his love of Mom, and for several years after Mom died, he sent them to his favorite women: his daughters in law, his niece and me. He still loved chocolate and enjoyed his last bowl of ice cream with chocolate sauce the evening before he died.

He cared about the future of the nation, and voted in his 19th presidential election last year. He still loved and worried about us, his adult children. I asked him once, “Do you ever stop worrying?” and he said, “No, never.” He often asked after his grandchildren, and even his great grandchildren.

I said this was a love story, and so it is. On the day my father died, he was agitated. His time was near, though we did not guess how near. At about 11 a.m., Maddie comforted him by reading poetry from the little book of his favorite poetry, “Henry’s Passages.” She read Longfellow, and Shelley, and, of course, Shakespearian sonnets.

Around 3 p.m., after being unresponsive most of the day, Dad suddenly smiled. And shortly before 6 p.m., his eyebrows lifted, as if he was seeing someone who delighted him. And his lips began moving as if he were speaking to that person. Dean and I felt that he was seeing Mom.

When Dean and I realized that Dad’s breathing suddenly changed at about 6 p.m., Dean held Dad’s hand, and I started reading Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130, which was the last sonnet Dad recited from memory, several days before. Then his breathing slowed, and finally stopped altogether.

Henry Snively Campbell – loving friend, son, brother, uncle, husband, grandfather, great grandfather, and father — died in a state of love, which is to say, a state of grace.

Henry Snively Campbell – loving friend, son, brother, uncle, husband, grandfather, great grandfather, and father — died in a state of love, which is to say, a state of grace.

Cheers, Dad.